Bloomery Steel of the Early Iron Age from Iberia. New Article

Background

Early iron metallurgy of the first millennium BCE is often described either as technically immature or as a sharp break from Bronze Age practice. Both views are too coarse. Our new study of a bloomery steel chisel from Rocha do Vigio shows a more gradual development (Asmus et al 2026).

The artefact

The object was made for a bloomery iron and is dated to the ninth century BCE. In an earlier study, we characterised the metal as bloomery steel and determined its carbon content. Quantifying carbon in hardened material is only partly reliable. For this reason, the first study focused on the body of the tool. The cutting edge was not examined at that stage (Araque Gonzalez et al 2023).

Based on a carbon content of about 0.5 wt% C and the early date of the artefact, we later investigated the tip itself. The aim was to assess whether, and to what extent, it had been thermally treated of it was hardened at all.

Bloomery steel: Microstructure and hardness

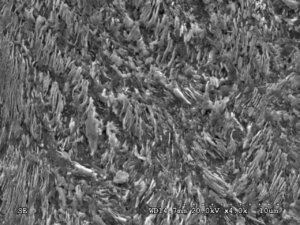

Metallography of the cutting edge shows a homogeneous and very fine pearlitic to pearlitic-bainitic microstructure. Ferrite is present only in small amounts. Martensite is absent. This points to accelerated cooling, but not to full quenching in the modern sense.

Secondary electron image of the chisel tip close to the cutting edge, showing mostly very fine pearlite, with some upper bainite in between the feathery colonies of the fine pearlite. Image: Asmus.

Vickers microhardness measurements show a moderate hardness gradient between the softer body and the refined tip. The values are consistent with controlled thermal treatment during forging. There is no indication that maximum hardness was the goal.

Alloy chemistry

The bloomery steel is low in manganese, as expected for early iron. Its hardenability therefore differs strongly from that of modern steels. Many commonly used transformation models are based on modern reference compositions. Our results show that these models are only of limited use for early iron artefacts. More accurate transformation data for low-Mn systems are – surprisingly – still lacking.

Production context

Slags from the site confirm local primary iron production. The chisel is part of a regional metallurgical practice. It is not an imported or exceptional object.

Taken together, the evidence points to a deliberate transfer of Bronze Age thermal working strategies to iron. Early iron metallurgy in this case reflects continuity of skill rather than a technological breakthrough.

The full article is available here:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2026.01.091