Bronze doors: Medieval Monumental Casting between Technology and Workshop Practice

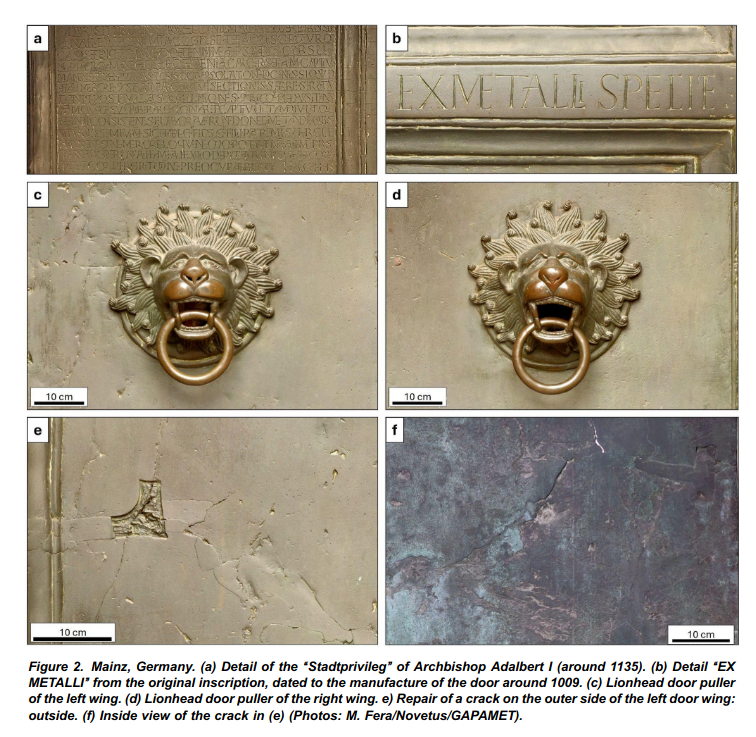

Monumental bronze doors of the High Middle Ages are most often discussed from an art-historical perspective. Their technical dimension has received far less systematic attention. Two closely related studies address this gap by examining the large bronze doors of Hildesheim, Mainz, and Augsburg from a materials-scientific and casting-technical point of view.

The first study takes a comparative approach to all three bronze doors (Mödlinger et al 2026). Based on alloy analyses and casting-related questions, it discusses material choice, casting strategy, and practical feasibility. The results show that the bronze doors are neither technically uniform nor best understood as isolated exceptional works. Instead, each reflects specific decisions, constraints, and priorities within its casting context.

The second study focuses on the Hildesheim bronze doors and places greater emphasis on process-oriented interpretation (Cziegler et al 2025). Casting simulations are used to explore thermal behaviour, solidification sequences, and potential risk zones during the pour. These models do not replace historical evidence. They help distinguish technically plausible scenarios from unlikely ones and allow discussion of possible workshop practices.

Medieval bronze bronze doors: Methodological approach

The methodological approach is central to both studies. The aim is not to describe medieval casting processes as if they were directly observed, nor to project modern metallurgical concepts back onto the Middle Ages. Instead, the focus lies on identifying the technical concepts, experiential knowledge, and problem-solving strategies that could realistically have been available at the time.

The analysis proceeds deliberately from a chronological bottom-up perspective. This is not meant in a hierarchical sense, but as an attempt to understand how casting practice developed through material constraints, process limitations, and workshop routines. The resulting interpretations are therefore necessarily plausible rather than definitive. They are intended to narrow the range of interpretation, not to close it.

Collaboration with Gates of Paradise Project

Both papers were developed in the context of a close collaboration with the GAPAMET project (Gates to Paradise), which focuses on the interdisciplinary study of medieval bronze bronze doors. Over the past two years, our laboratory has worked closely with the team led by Marianne Mödlinger, the project’s principal investigator. This collaboration provided the framework for many of the materials-science and casting-related questions addressed in these studies.

More information on the project:

https://www.gapamet.imareal.sbg.ac.at/en/

A related post from this collaborative context, led to a separate paper (Asmus et al 2025) on specific workshop practices and means of replicating (wax) models.

Articles

The articles are available here:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-025-01857-4

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-025-01820-3