A Romanesque Bell for a Romanesque Chapel

Visiting the amazing bell foundry Grassmayr in Innsbruck, Austria, which houses the Romanesque bell from Hachen.

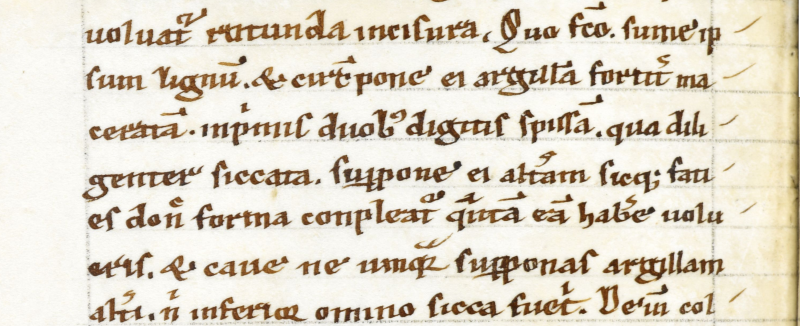

A Romanesque bell for the Romanesque Bartholomew chapel! What a fantastic development based on experimental archaeology! After working since 2015 on the reconstruction of the bell casting technique described by Theophilus Presbyter , which finally led to the long-awaited bell for the Campus Galli earlier this year, there is another step to be made: For not only does the metropolitan chapter of Paderborn want the public to experience how a Romanesque bell was cast around the year 1000, no, this bell is to be installed in the Romanesque Bartholomew Chapel, which celebrated its 1000th anniversary in 2017.

The Bartholomew Chapel is not just any Romanesque chapel, it is an important architectural achievement of the high Middle Ages, which with its Byzantine style elements has no direct precursors or subsequent buildings. This oldest hall church in Germany was built in the Ottonian period as a palatine chapel during the construction of the new Paderborn palatine.

The Bartholomew chapel in Paderborn, dated to the early 11th century. The ridge turret is still empty! There the new Romanesque bell will be installed.

A Romanesque bell in the making

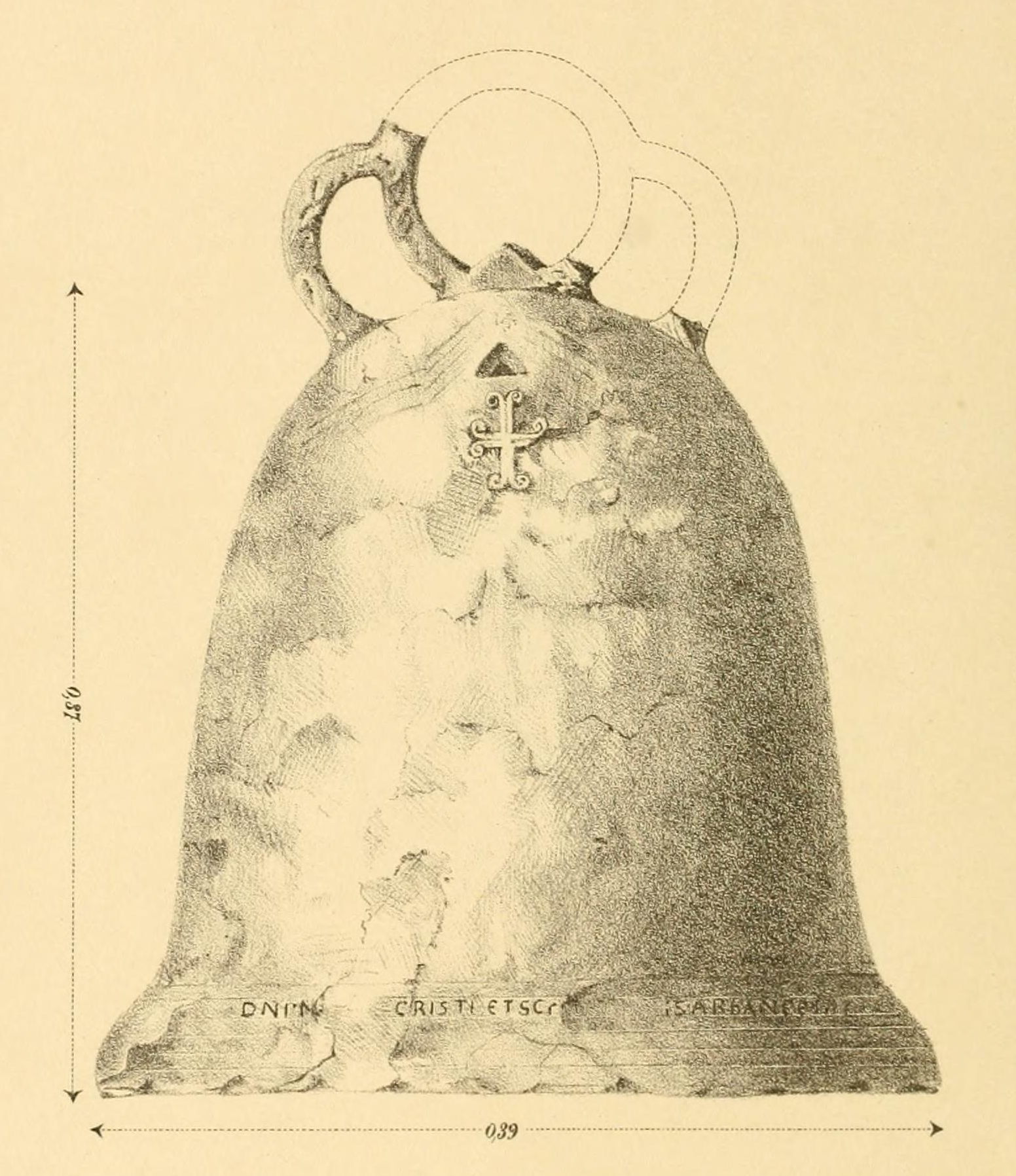

The St. Bartholomew’s Chapel is given a bell that matches its date of origin. As a model for the new bell, a Romanesque bell from North Rhine-Westphalia was chosen. The bell of Hachen can be admired today in the bell museum of the bell foundry Grassmayr in Innsbruck, which acquired the bell in 1938 from the bell foundry Heinrich Hupert from Brilon. The Grassmayr brothers allowed me to measure the bell exactly, so that a new creation of this bell type can succeed. This is not about making an exact copy of the Hachen bell. Rather, it can be seen as a model for casting a “new Romanesque” bell. The technology of bell casting is similar to that used to make the Canino bell, i.e. the lost wax process as described in Theophilus Presbyter.

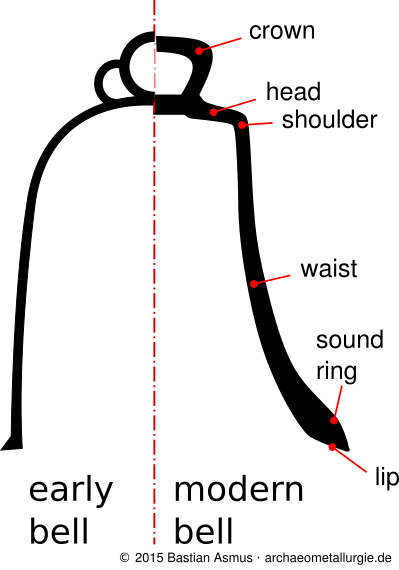

The Romanesque bell from Hachen is housed in the bell museum Grassmayr in Innsbruck. In comparison to the much older Canino bell, this bell exhibits a much more pronounced waste and shoulder section.

By 1017, the church had already had at least two centuries of experience in the casting of bells. In addition to increased wall thickness of the rib the shape has also developed from an egg-shape to a more pronounced waist and shoulders. Also the sound holes are often only present as a typological rudiment. Next to the technical casting questions, here are a few questions concerning the conceptual side of bell development:

- can the different dimensions of the bell be put in a certain ratio?

- how was a bell designed in the Middle Ages?

- what were the measurement options?

- how exactly can the sound be predicted?

All ribs of contemporary bells were studied and compared. Drescher has already done very valuable work here , and many of the ideas presented here have their basis in his work.

Digression: The fingerprints of the Hachen bell founder

During the examination of the Hachen bell I discovered the fingerprints of my colleague who left them in the bell model a 1000 years ago. Even for an archaeologist this was an extremely impressive moment. It also goes to show the surface quality the casting method was capable to produce.

A 1000 years old fingerprints of my “colleague” in the handle of the Romanesque bell from Hachen! Width of the handle shown: 33mm.

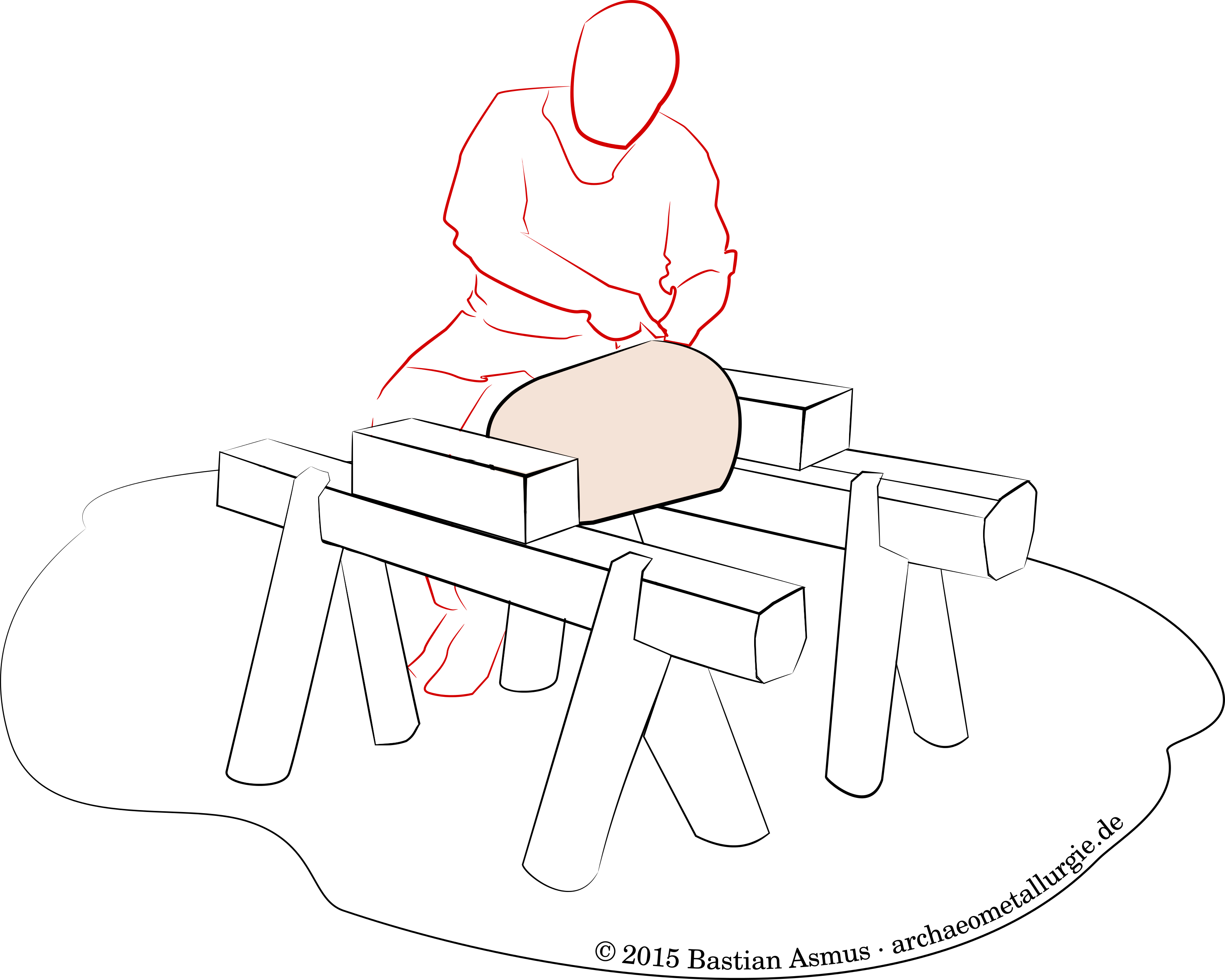

Still no strickle board in the Romanesque period

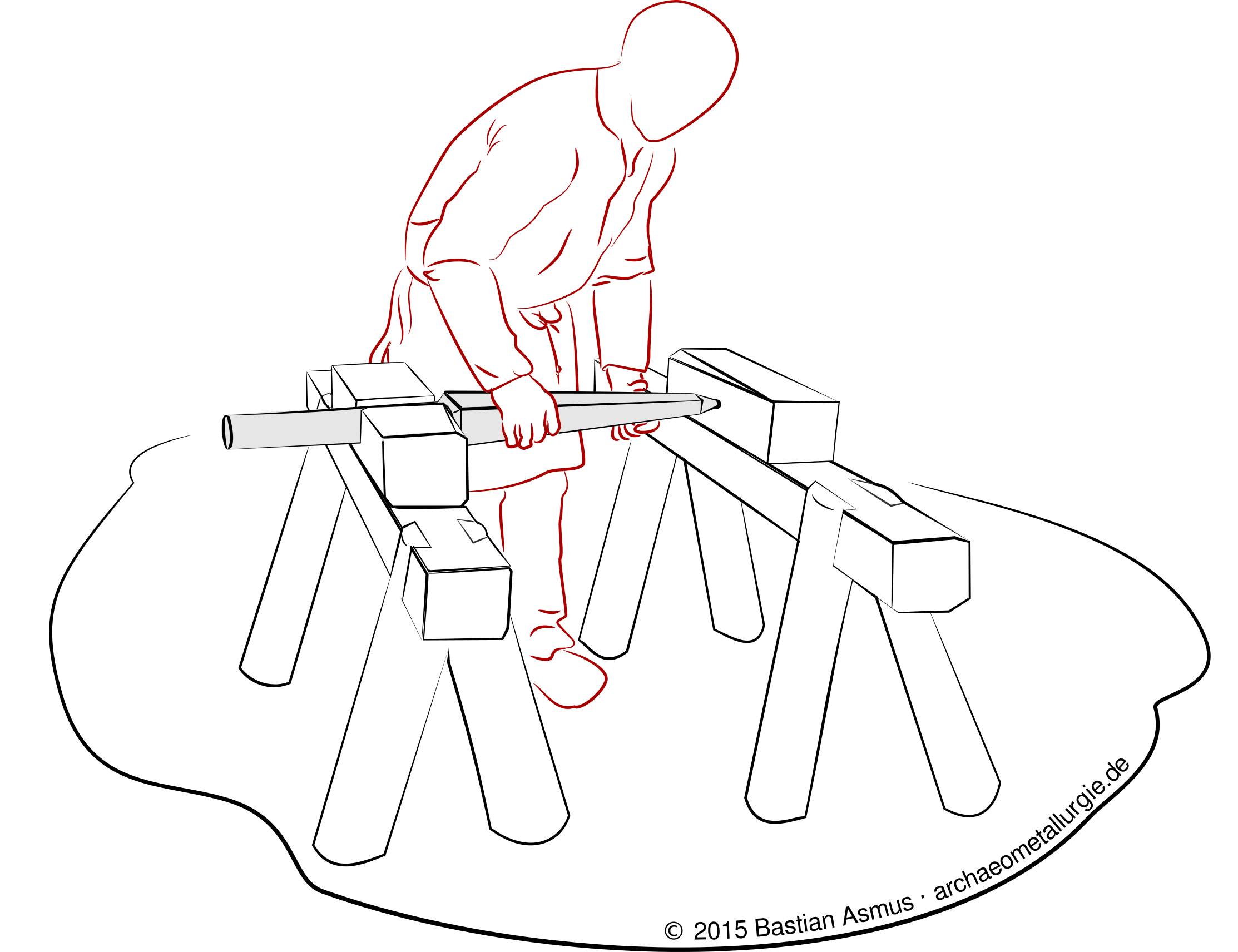

How can we imagine the manufacturing process? Has a cleric seen another bell and developed a desire to also possess a bell? Was this wish expressed like: “I would like a bell like the one from Mainz” or was it completely different? I don’t think I can answer those questions that quickly. But since Theophilus still does not speak of the use of a strickle board a hundred years later, we must assume that the ribs of the bells were made in a different way. A direct comparison of different ribs was therefore not possible in the medieval period. This would explain also explain why the sound finding of the early bells had to be based on chance at first. It is assumed here that only the documentation of the bell rib may have led to controlled experiments on the influence of the rib on the sound.

The production of the Romanesque bell for Paderborn poses a similar problem for me. I have a client who knows a bell he’d like to have. I can look at the bell and measure it, but I cannot use the strickle board to to transfer the rib, as this was unknown in the 11th century. I can transfer the dimensions recorded with the gripping compass with the gripping compass. This inevitably results in inaccuracies which, however I suspect were not a problem then. Nevertheless, during working at the bell you wonder whether there were any underlying rules to lay out the measures. Drescher proposed that the diameter of the sound bow provided a base measure, from which the rest of the bell may have been constructed.

The Hachen bell has a height to sound bow ratio of 5:4, as well as a ratio of the diameter at the shoulder to the total height of the bell 1:2, and a ratio of about 1:1 strike ring diameter to the height of the sounding body. Further clear ratios could not be determined so far, in particular to the curvature of the bell waist.

Documentary

The project is documented as a video log and recorded in several short films. So far, the first four working days have been completed. Note that working days are not the same as the process days, as the relatively massive casting core takes several days to dry. So far, the process has been ongoing since June 23, 2018, so that eleven process days have already passed by the time this article is written (July 3, 2018)

Day 1 and 2 Romanesque bell – setting up shop and making of the core

Day 3 and 4 Romanesque bell . finishing the core

Day 5 and 6 Romanesque bell – making of wax model

Day 7 to 10 Romanesque bell – finishing the wax model

Tag 11 bis 15 Romanesque bell – mould, pit and furnace

Tag 16 bis 18 Romanesque bell – Casting the bell!!

References