Successful Carolingian bell-founding

Carolingian bell-founding on Campus Galli

A Carolingian bell for Campus Galli has been cast successfully. Three experiments were necessary to cast a complete bell. On 28.4.2018, for the first time in hundreds of years, a Carolinigina bell was successfully cast according to the treatise of Theophilus Presbyter. The sound is already breathtaking – although the bell has not yet been worked on – and shows the harsh sound so typical of for these early bells. I am thrilled! The bell of Canino, the earliest known bronze cast church bell is the model for the bell that we cast in this experiment. It was not only reconstructed to the original dimensions, but more importantly, its original production method was also reconstructed, following the excellent medieval manuscriput of Theophilus Presbyter]. Thus the bell-founding experiments on the Campus Galli have finally come to a happy end. The bell can still be regarded as a raw casting on the Campus Galli until Whitsun. Then, after I have finished it, it will be installed on campus.

Applied archaeometallurgy: The crown of the Carolingian bell of experiment no. 3 form 2018.

The bell

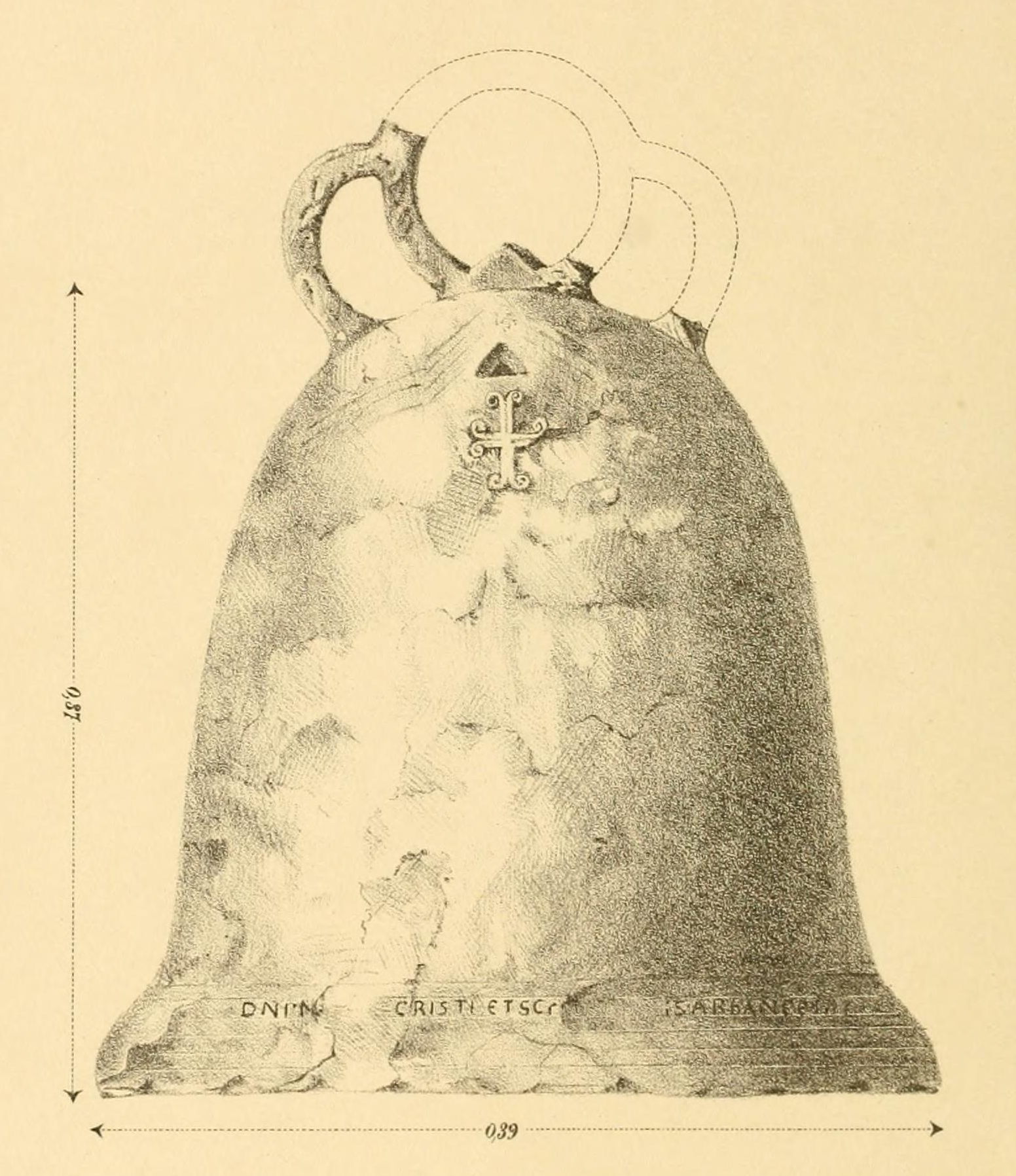

The shape of the beehive bell is based on the oldest known cast bronze bell: the Canino bell. It has a diameter of 39 cm at the sound ring and weighs 44 kg. Note the triangular sound-holes of this bell from the 8th/9th century. Theophilus also describes them in the 12th century in his bell-founding chapter. According to the unanimous opinion of the bell entrepreneurs, however, these do not contribute to the sound.

Drawing of the bell of Canino in the original publication [zotpressInText item="{4ICDYHGU}"].

Carolingian bell casting in the Middle Ages can only be achieved in a team effort

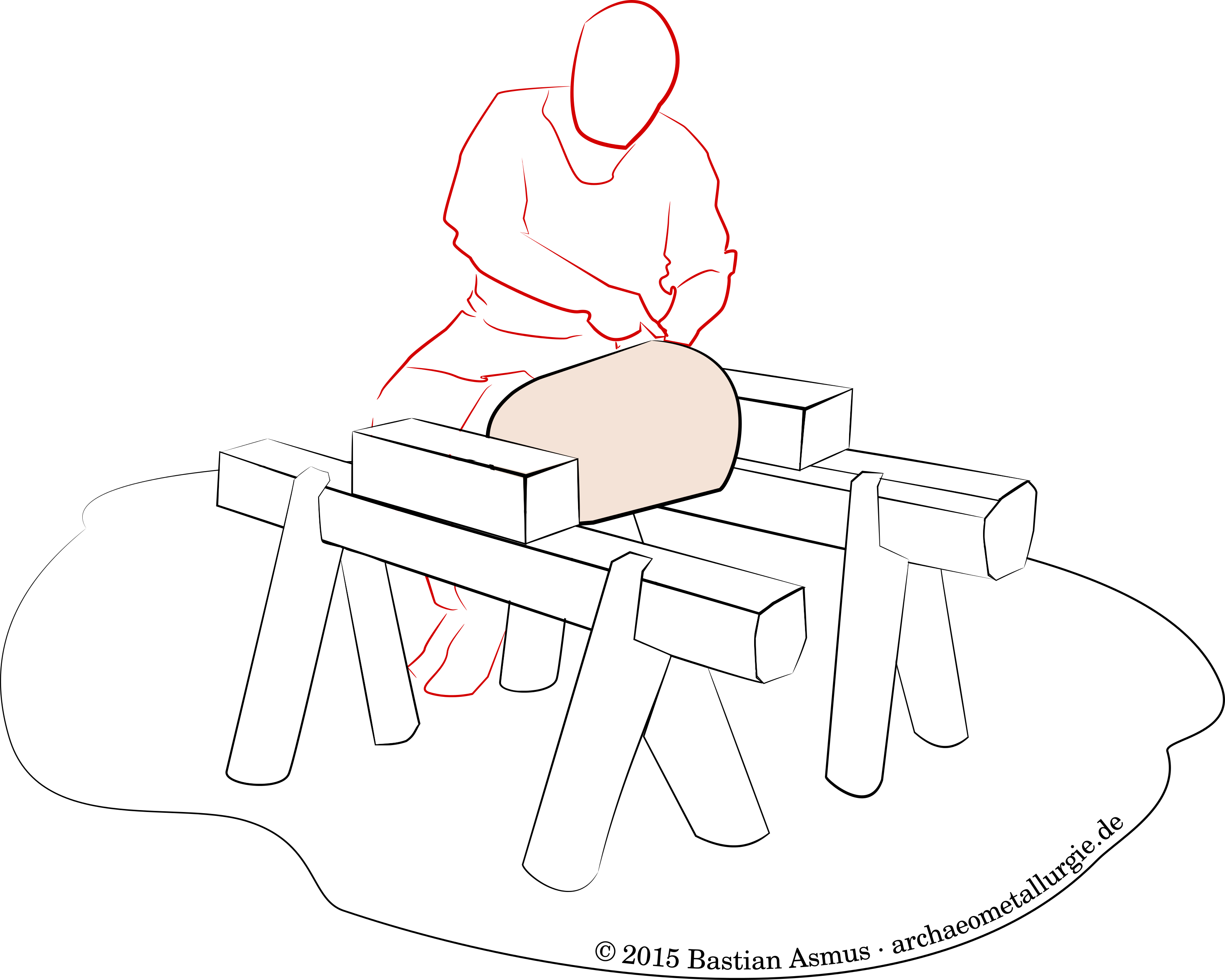

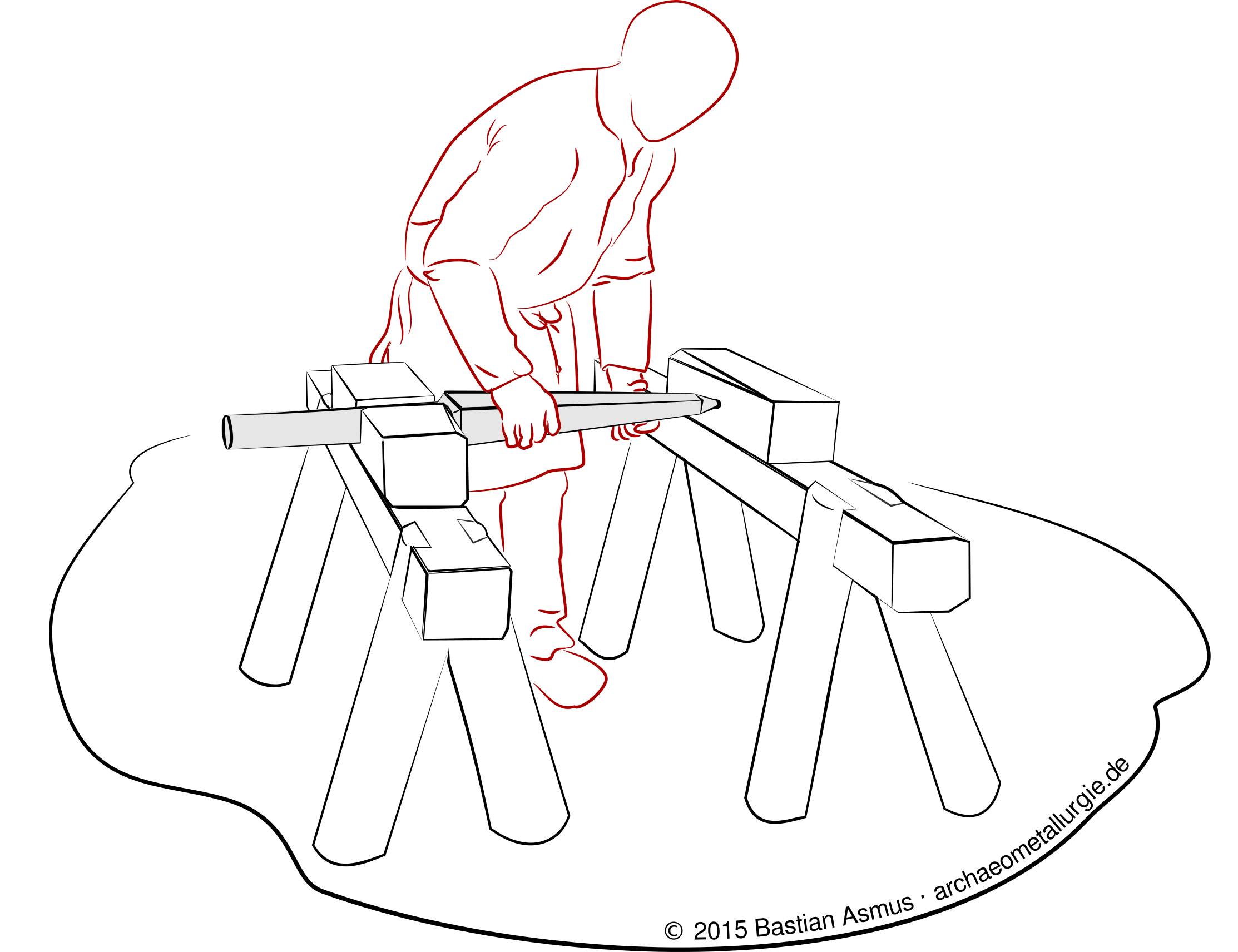

Large lathe for bell-founding. Making the core . Unlike later, early bells were made horizontally, and in the lost-wax process!

Besides many technical details which will be discussed later on, the most important conclusion is that a large and well-coordinated team is necessary to successfully master the bell-founding process. This year we have succeeded in doing this in a particularly good way. This also allows some conclusions for the past, because good communication is necessary to successfully execute the entire process.

Previous experiments and some background on medieval bell-founding

Some time ago I started a larger project: the casting of a medieval bell. To that end I spend some time at the Campus Galli near Meßkirch, south western Germany. At the weekend of the 27./28. June 2015 a core of the bell was made. The casting of the medieval bell will take place from September 16 to 20. The Campus Galli is project that aims at building a Carolingian monastery with authentic methods only. The Campus Galli thus provided an excellent infrastructure to conduct this archaeometallurgical experiment. In the first part of this report we will talk a bit about the history of bells, where they are concerned with Christianity, in the second part I will discuss the manufacturing process and in the third part I will report on the experimental reconstruction of the casting of a medieval bell.

A very incomplete introduction to early church bells

The oldest surviving church bell is the bell from Canino, Upper Italy. It stems from the 8th/9th century and is now at the Vatican museums.

Cast bells are much older than Christianity and the earliest cast bronze bells are small clapper bells found around pre-Shang China, roughly 1900-1600 BC , but this shall not be of further interest here. The oldest surviving cast bronze church bell is from the ninth century AD. It is the bell of Canino in Upper Italy , nowadays housed in the Vatican museum . From the fifth century bells were used by Christians.

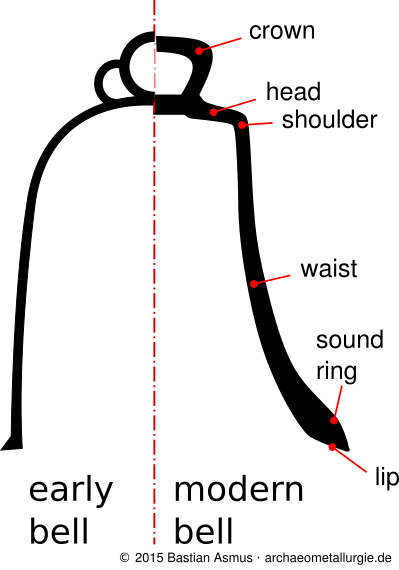

The bells from the 8th to the 12th century did differ in several respects from bells we know nowadays. They possessed a different shape, reminiscent of old beehives. Because of the simpler shape and the sound. The sound of the bells was less defined than today. The following sound snippet is from the oldest resonant bell still in existence in Germany:

via wikimedia commons, User: 2micha

It is the sound of the Lullus bell from Bad Hersfeld, Hassia, cast in 1038 AD. The image to the left shows the differences in the bell shape. The early church bells were more or less of a uniform thickness throughout. In the beginning there was no sound ring of any note. This only evolved over time and the differences in thickness, which are responsible for the sound, became more pronounced in the following centuries. Another difference is the mode of production, whereas modern bells foundries use a two part mould, which is made using a clay model of the bell, until the 12th or 13th century AD bell founding relied on the lost wax method.

Shape of bells in the 9th century compared to modern times.

Experiences and observations made

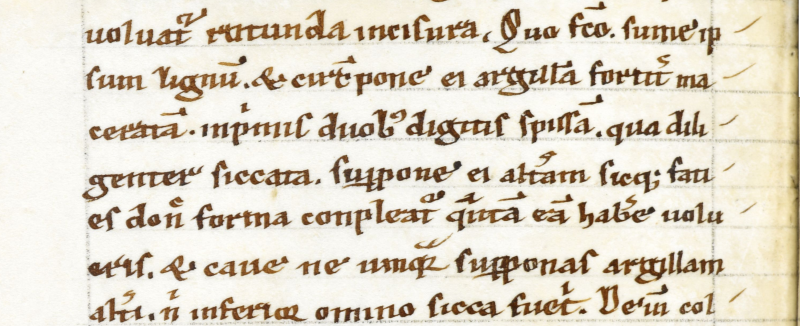

My experience of the broken core can also be read indirectly in the schedula diversarum artium of the Benedictine Theophilus Presbyter for bell casting .

Detail from Theophilus Presbyter’s de diversis artibus, Harley MS 3915. We see Theophilus warning to dry each layer of core clay properly, before applying the next one.

Quo facto, sume ipsum lignum et circumpone ei argillam fortiter maceratam, inprimis duobus digitis spissam, qua diligenter siccata, suppone ei alteram, sicque facies donec forma compleatur quantam eam habere volueris, et cave ne unquam superponas argillam alteri nisi inferior omnino sicca fuerit.

Once that is done, take the wooden spindle and cover it with vigorously worked clay, first of two fingers thickness. Is this thoroughly dried, put the next about it, and repeat this until the mould is ready, as big as you want it. And make sure that you never apply a layer on the other before the underlying clay is completely dry.

His insistent warning is not followed by a consequence, but it can be assumed that similar mishaps happened to the craftsmen of that time: If you don’t follow the instructions – for example to keep to an ambitious schedule – what happened to me happens: The (too) damp clay core breaks out of each other. Why is that so?

The clay core is made in horizontal fashion i.e. as long as the moulded clay is damp, it tends to tear off as it hangs freely. If the clay is too damp, it tears off due to its own weight. Perhaps this is also one of the reasons why from the 13th/14th century on one started to form bells standing. Here the moulded clay can also move when moist, but the clay core does not hang freely, and nothing can tear off. The worst that can happen is that the core collapses a little.

The clay core of the bell is mounted on a wooden spindle. Unlike later centuries, Carolingian bells are shaped horizontally. Image: rk-film.de

See the following images for an illustration how the core is made

Inserting the spindle in the large lathe.

Loam is applied in layers to an oaken wood spindle. Each layer should be well dried before applying another layer. Theophilus suggests layers about two fingers thickness. These layers can be dried relatively easily with a small fire under the revolving spindle, however wind works even better. Since the core is mounted horizontally, the weight of the core acts on the freely suspended part of the core. The problem is the total moisture content of the core, because a moist core tends to tear apart. If the core becomes too heavy, it tears apart in the middle.

Schematic of the bell core: 1. wooden spindle 2. first loam layer 3. second loam layer 4. competed core 5. wax model of the bells body.

The addition of straw and horse manure – sometimes referred to as organic tempering counteracts this by producing a fibre composite. The organic fibres in the moulded clay increase its tensile strength. De facto this means that the thus treated, very lean moulding loam has improved plastic properties in the moist state. This results in a sufficient stability not to tear apart. In addition, the organic admixture increase moisture transport and reduces drying times. Moreover, during firing of the mould these fibres burn and ensure improved gas permeability of the moulding material.

Second last layer of core loam. Photo: © Simone Napierala 2015.

The last layer of the mould core consists of fine moulding loam, so that the surface of the casting becomes smoother. It has no addition of straw, only the fibres of the horse manure.

Nevertheless, some challenges remain

Although the bell is complete, the properties of the moulded clay to be examined have also led to undesirable effects. On the one hand, only a poorer casting surface quality was achieved this time, and on the other hand, the mould broke for the first time. By damming and prudent action during casting, the bell could be saved, even though the mould broke below the handle. Nevertheless, this has had a negative influence on the handle, which is clearly visible at the top of the picture.

Future work

The next bell I will cast this way is the Hachen bell. Today it can be seen in the Glockenmayr Museum in Innsbruck, Austria. I am allowed to measure due to the courtesy of Johannes Grassmayr in the museum there. In this experiment the focus is on the refinement of proven moulding loams.

References

Reconstruction: Early 15th century tap. The location is Zurich, Switzerland.

Reconstruction: Early 15th century tap. The location is Zurich, Switzerland.