Wiltu ein puchsn gießn sei sy gros oder klayn – if you want to cast a gun be it big or small

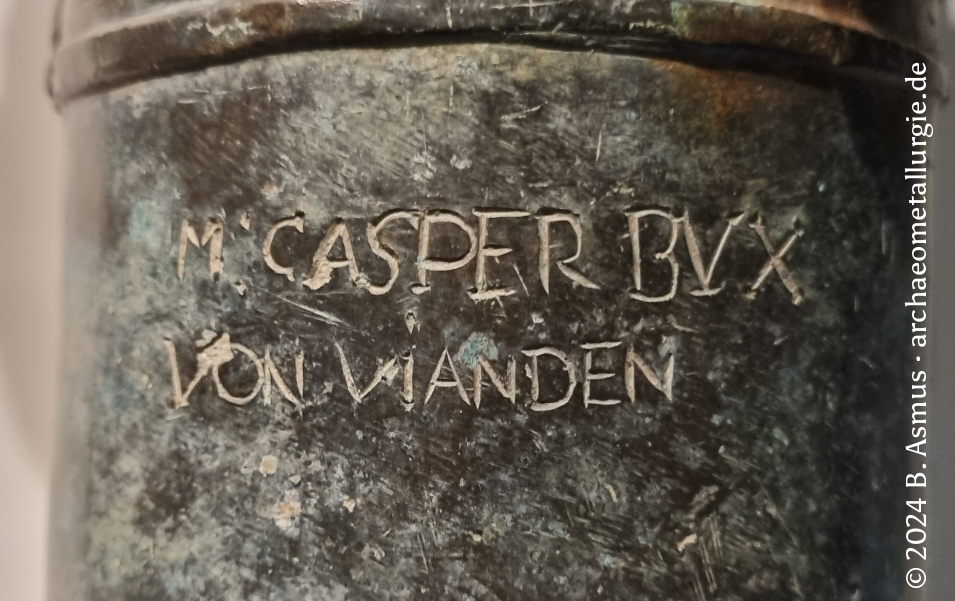

The Danzig handgonne is an unusual very early form of a firearm. The handgonne is unusual because it shows a three-faced representation at the muzzle. It is interpreted by some colleagues as a representation of the Slavic god Triglav

VIDEO

How old is the handgonne from Danzig?

Unfortunately, the Danzig handgonne cannot be dated precisely because the circumstances of its discovery are unclear. We know the approximate find date: around the 1920s. There are two competing statements with regards to its find location (Petri, 2017, 222):

It is from the area of Schwedt, from a pond on an estate.It is from near the city of Gdansk, and turned up during dredging operationsThe Danzig handgonne was privately owned for a long time, and was auctioned at Christies in 2014. Today it is in the collections of the Royal Armouries in England. Based on stylistic features, the handgonne is believed to have been made between the mid-14th and early 15th centuries AD.

In this video, I show you how I would have cast the Danzig handgonne in the late Middle Ages using the lost wax process. I first modelled an original wax. Then I made a mould out of a refractory material: moulding loam. When the mould is fired, the wax issues from the mould, leaving the mould cavity in the hardened loam. The bronze can be poured into this. For demoulding, I have to break the mould: the mould is now lost, so each casting is unique….

I will also show you how to finish the Danzig handgonne barrel. Burrs have to be removed by chisel, the surface has to be finished in some places with the file and the scraper. Finally, I make the ash stock for hand rifle. It is a simple bar stock, as we know it for example from the Landshut Zeugausinventar.

Which material?

Unfortunately, there are no exact composition analyses of the handgonne available until today. It is definitely a copper alloy, brass is ruled out for the period and region. That leaves copper and tin bronze. Strong copper rich alloys are an unsuitable material, but these were actually used as recent investigations on another firearm show (Asmus & Homann, in prep). In addition, the numerous accounts on the bombards from the Teutonic Order area show that copper was apparently used for gun casting

As an archaeometallurgist from the Laboratory for Archaeometallurgy, I study the metallurgy of our ancestors. For this I use my craft as an art founder, the historical and archaeological disciplines, as well as the material science disciplines of the natural sciences.

Literature

{1698736:89N5JX6X};{1698736:V6PQ9UF4 }

apa

default

asc

0

3175