Sep

19

2013

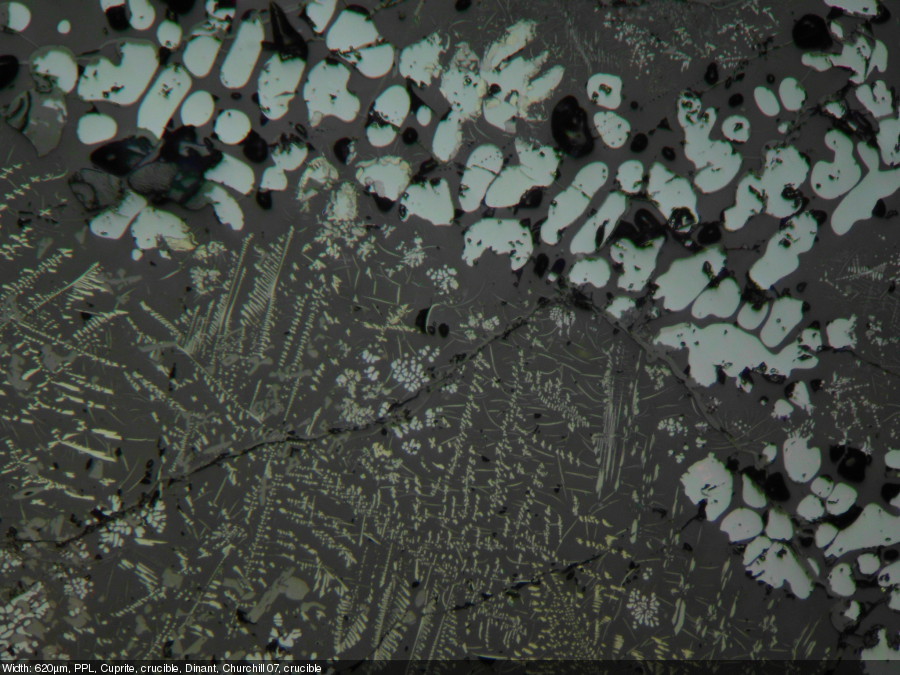

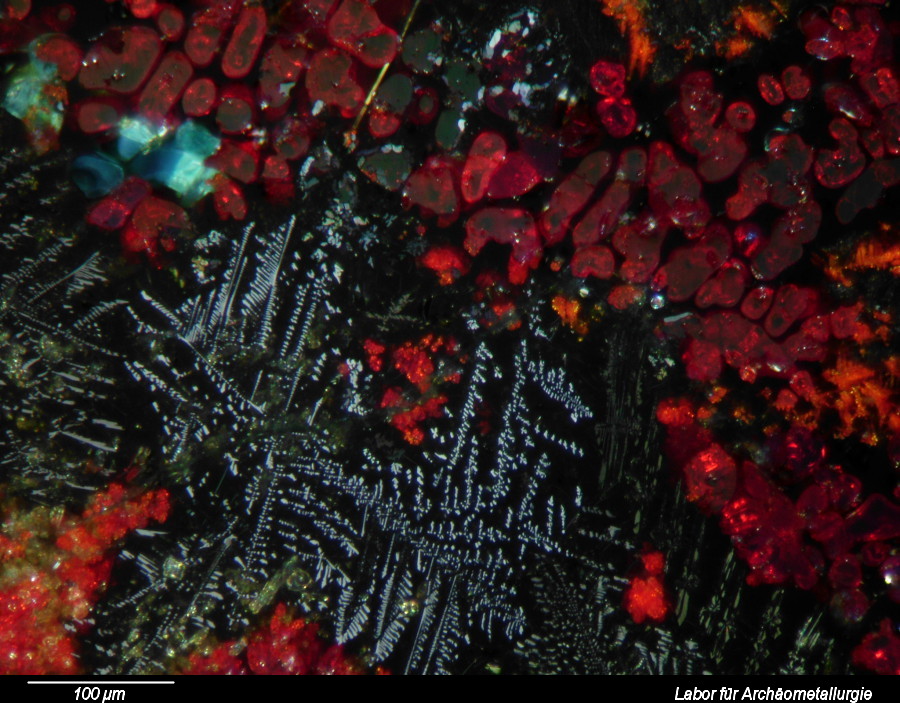

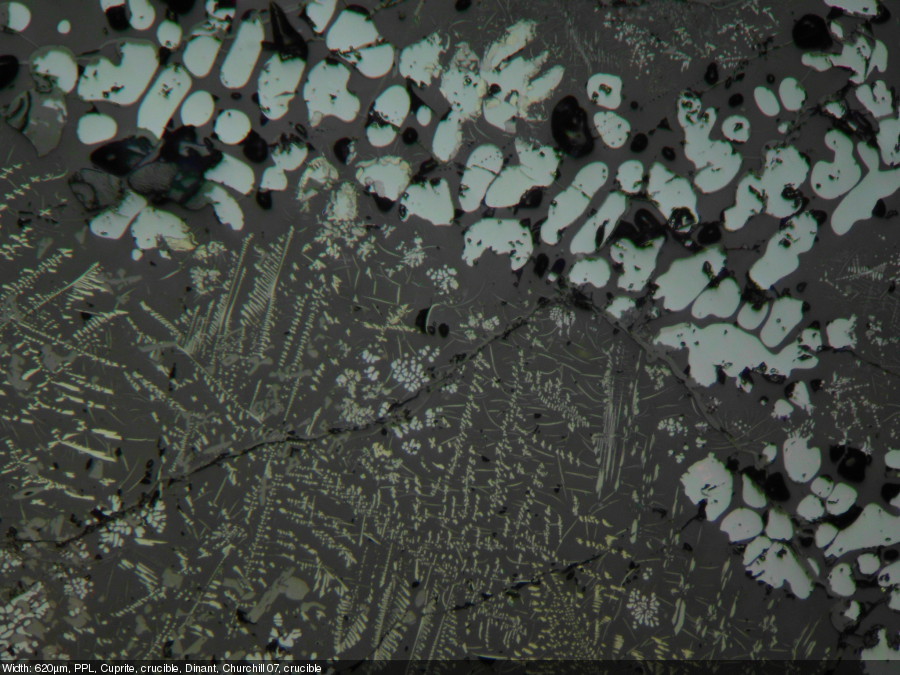

Bastian Asmus

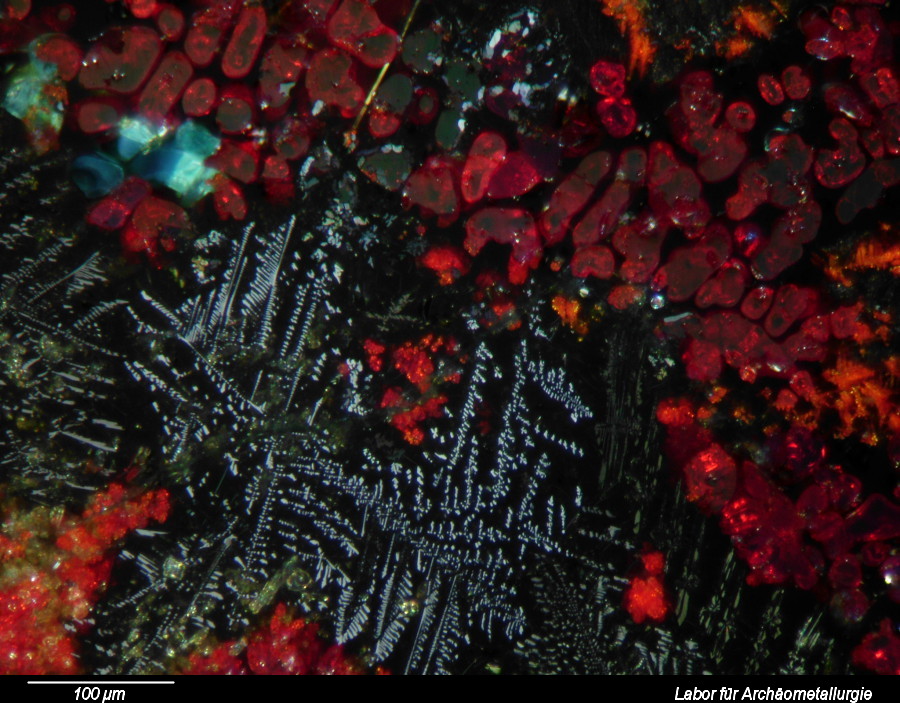

This post describes three of the many possible ways of annotating micrographs with a scale bar: manually, semi-manually and fully automated. Any meaningful micrograph needs a scale as a means of informing us about the size of the documented microscopic structutres. There are two ways possible: Either use the caption to tell us the image width, or annotate the image with a scale bar. The left image (click!) informs us about the image in an unobtrusive bar at the bottom of the image, the right image shows the solution with the scale bar.

1. Annotating micrographs manually

2. Making scale bars – Using Scientific Image manipulation software ImageJ

3. Annotating micrographs using meta tags and a simple shell script

3 comments | tags: Digital Asset Management, How to, microscopy | posted in Archaeometallurgy, Micrograph

Jun

30

2013

Bastian Asmus

[tab: Description]

Bastian Asmus 2012:

Medieval Copper Smelting in the Harz Mountains, Germany (= Montanregion Harz, Bd 10 [Hg. Christoph Bartels, Karl Heinrich Kaufhold und Rainer Slotta]), Bochum (Veröffentlichungen aus dem Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum Nr 191), 2012, ISBN 13: 978-3-937203-63-8

395 pages, english, colour, Appendix for microscopic identification (reflected polarising lihjt microscopy) of slag phases, metal phases, ore minerals and their analysis by SEM-EDS, WDX and EPMA-WDS as well as XRF for bulk chemical characterisation.

44,- Euro

Medieval copper from the Harz

The work deals with the evaluation of a high medieval smelting site in the Harz, near the UNESCO World Heritage sites Rammelsberg and Goslar. With more than 1000 m2 excavated it is to date the most extensive archaeometallurgical investigation of a smelting site in medieval central Europe. It is a site where the polymetallic Rammelsberg ore was smelted to produce copper, lead and silver. The site can be considered as a typical example of a high medieval smelting site in the Harz. Particular emphasis was placed on an interdisciplinary approach which drew upon historical, archaeological and material scientific sources.

[tab: abstract]

Abstract

The Rammelsberg deposit in the Harz mountains in Germany is among the largest metal deposits in the world and has been in continuous use for more than a millennium. There is much controversy as to the nature of the metals produced and the processes involved from the ores of this deposit. This thesis deals with the largest and most accurately excavated smelting site of the high medieval period in the Harz mountains called Huneberg and may be regarded as typical for region and period.

Traditionally historians connect the Rammelsberg with silver production, the mining historians, however point out that the deposit is too poor in silver and that copper was produced in the high medieval period. Modern economical literature classifies the Ram- melsberg as a lead-zinc deposit.

To contribute towards the understanding of these questions an archaeometric study of archaeometallurgic waste- and byproducts, such as slag, furnace lining, furnace wall, litharge and spilled metal drops was undertaken. It builds the base of the interpretation of the metallurgical activities that have taken place at the Huneberg and is contrasted with previous studies. It is suggested that copper, lead and silver in form of argentiferous lead were produced on site, using a complex multi-step process, taking full advantage of the numerous structural features of the site, e.g. the three furnaces present on the site. Successive smelting episodes produced black copper of increasing purity as well as a rather rich argentiferous lead. Because the site is similar to may other sites it is further suggested the mode of metal production at the Huneberg followed a more or less stringent set of recipes and traditions. The mass of 1600 kg slag recovered from the site suggest a copper production of some 600 kg or less, depending on the ore quality. Lead is thought to have been produced in similar quantities, which in turn would mean that the site produced also 1.4 kg of silver during its operation.

[tab: Order info]

Order

44,- Euro plus P&P

Online shop of the German Mining Museum

[tab:END]

no comments | posted in Archaeometallurgy, Science

Jun

27

2013

Bastian Asmus

A lion aquamanile from Halberstadt, Germany

A lion aquamanile from Halberstadt, Germany

The lion aquamanile you can see here I modelled after the aquamanile from Halberstadt. It is to date one of the very few aquamaniles that is still in its original context (Mende 2008). Aquamaniles, somtimes also referred to asaquamanale, aquimanile, aquamnilia is composed of the the two latin words aqua, for waterr und manus, for hand. The term aquamanile was used differently in medieval times than today: it mostly referred to the receptables of the water in the form of dishes or bowl. In contrast the vessel for pouring water was called urceus, i.e. latin for ewer (Wolter-von dem Knesebeck 2008, 217). Aquamaniles were used for the ritual cleansing of the priest before the mass. Apart from this ecclesiastic use aquamaniles were also to be found in secular households of high social status where they were used before meals.

Detail shot of the wax model

During the last month or so I modelled this 13th century aquamanile and cast it in bronze in my casting workshop using the lost wax technique. The model was made from wax and was prepared over a core of loam, just as it was described by the benedictine monk and artificer Theophilus Presbyter in his schedula diversarum artium in the chapter on the production of the cast incense burner. See here how the article on the casting of the aquamanile went in the reconstructed medieval loam mould.

To this end wax plates were applied to the loam core. This is also described by Theophilus. An alternative way to produce a wax layer of sufficient thickness would have been the repeated dipping into liquid wax. This however was not mentioned by Theophilus and therefore not used. After the wax plates had been applied the finer details, such as the mane or the eyes of the lion were shaped.

Detail shot of the aquamaniles face

The aquamanile weighs 3,6 kg and holds 1.35 l of water. This reconstructed aquamanile may be seen in its original function at the events of the french re-enactment project Fief et chevalerie. Contact me if you would like to purchase this or any other aquamanile.

References:

Ursula Mende 2008.

Catalogue entry 52 in: Michael Brandt (Hrsg), Bild & Bestie. Hildesheimer Bronze der Stauferzeit. 378p. 2008.

Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck 2008.

Zur Inszenierung und Bedeutung von Aquamanilien, in: Michael Brandt (Hrsg), Bild & Bestie. Hildesheimer Bronze der Stauferzeit. 2008.

Medi bronze aquamanile in the form of a lion

Image 1 of 7

Dies ist eine Neuschöpfung des mittelalterlichen bronzenen Löwenaquamaniles von Halberstadt.

Das Original ist im Halberstädter Dommuseum.

This is a lion aquamanile that was made after the medi bronze aquamanile of Halberstadt. The original is in the Halberstädter Dommuseum.

2 comments | tags: Aquamanile, aquamanilia | posted in Aquamanile, Archaeometallurgy, General, Metal casting, practical metallurgy, Reconstructions