Jan

20

2026

Bastian Asmus

Background

Early iron metallurgy of the first millennium BCE is often described either as technically immature or as a sharp break from Bronze Age practice. Both views are too coarse. Our new study of a bloomery steel chisel from Rocha do Vigio shows a more gradual development (Asmus et al 2026).

A composite mesoscopic image of the sampled bloomery steel chisel-tip. © 2025 Bastian Asmus

The artefact

The object was made for a bloomery iron and is dated to the ninth century BCE. In an earlier study, we characterised the metal as bloomery steel and determined its carbon content. Quantifying carbon in hardened material is only partly reliable. For this reason, the first study focused on the body of the tool. The cutting edge was not examined at that stage (Araque Gonzalez et al 2023).

Based on a carbon content of about 0.5 wt% C and the early date of the artefact, we later investigated the tip itself. The aim was to assess whether, and to what extent, it had been thermally treated of it was hardened at all.

Bloomery steel: Microstructure and hardness

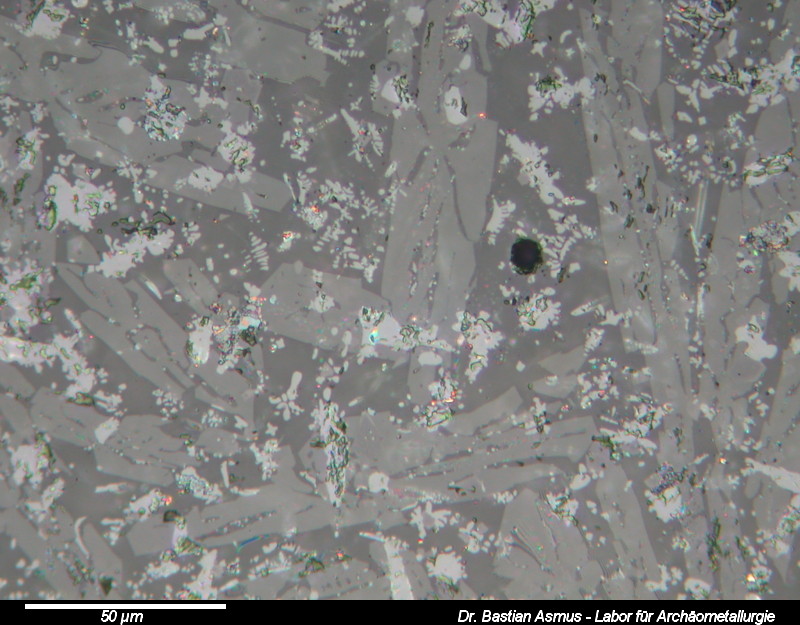

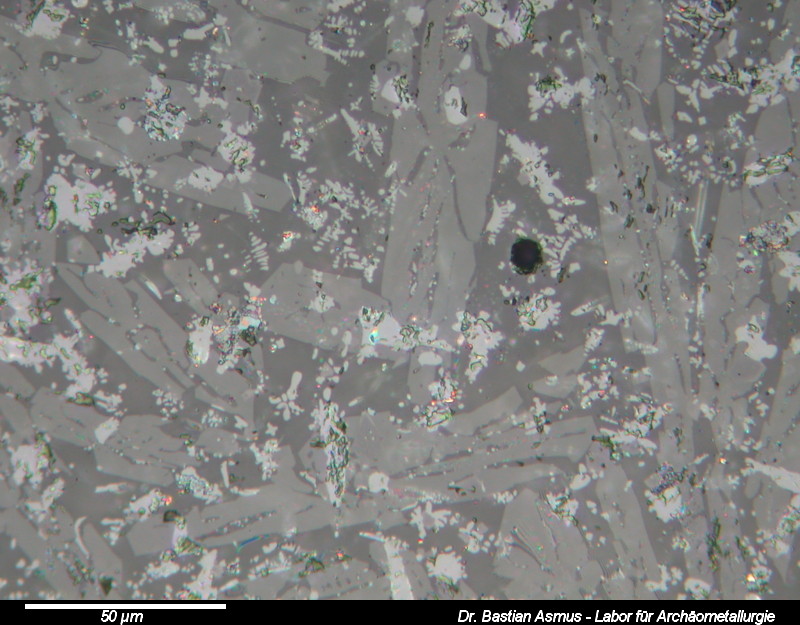

Metallography of the cutting edge shows a homogeneous and very fine pearlitic to pearlitic-bainitic microstructure. Ferrite is present only in small amounts. Martensite is absent. This points to accelerated cooling, but not to full quenching in the modern sense.

Secondary electron image of the chisel tip close to the cutting edge, showing mostly very fine pearlite, with some upper bainite in between the feathery colonies of the fine pearlite. Image: Asmus.

Vickers microhardness measurements show a moderate hardness gradient between the softer body and the refined tip. The values are consistent with controlled thermal treatment during forging. There is no indication that maximum hardness was the goal.

Alloy chemistry

The bloomery steel is low in manganese, as expected for early iron. Its hardenability therefore differs strongly from that of modern steels. Many commonly used transformation models are based on modern reference compositions. Our results show that these models are only of limited use for early iron artefacts. More accurate transformation data for low-Mn systems are – surprisingly – still lacking.

Production context

Slags from the site confirm local primary iron production. The chisel is part of a regional metallurgical practice. It is not an imported or exceptional object.

Taken together, the evidence points to a deliberate transfer of Bronze Age thermal working strategies to iron. Early iron metallurgy in this case reflects continuity of skill rather than a technological breakthrough.

The full article is available here:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2026.01.091

References

Araque Gonzalez, Ralph, Bastian Asmus, Pedro Baptista, Rui Mataloto, Pablo Paniego Díaz, Vera Rammelkammer, Alexander Richter, Giuseppe Vintrici, and Rafael Ferreiro Mählmann. ‘Stone-Working and the Earliest Steel in Iberia: Scientific Analyses and Experimental Replications of Final Bronze Age Stelae and Tools’.

Journal of Archaeological Science 152 (April 2023): 105742. doi:

10.1016/j.jas.2023.105742.

Asmus, Bastian, Ralph Araque Gonzalez, Rui Mataloto, Marc Gener-Moret, Pablo Paniego-Díaz, and Pedro Baptista. ‘Negotiating between Iron and Bronze Traditions: The Impact of a Tool – The Chisel from Rocha Do Vigio’.

Journal of Materials Research and Technology 41 (1 March 2026): 1615–29. doi:

10.1016/j.jmrt.2026.01.091.

Comments Off on Bloomery Steel of the Early Iron Age from Iberia. New Article | posted in Analysis, Archaeometallurgy, General, History, Micrograph, Science, slag

Nov

14

2017

Bastian Asmus

Non- ferrous sheet metal: Custom made historic red brass alloy,

Non-ferrous sheet metal

Who is not familiar with this, you want to make an object from non-ferrous metal sheet of a certain alloy, e. g. a helmet of the Urnfield period. But try as you might no sheet metal of the desired alloy can be obtained in the industry. The industry is simply not interested in supplying small and micro-enterprises or cultural science research projects. But that is no longer the case, as the Archaeometallurgy Laboratory has acquired a medium-sized rolling stand, where sheets up to a maximum theoretical size of 500 mm width can be rolled, though in reality a width of 450 mm is more likely to succeed. This is done in a purely hand-crafted process and thus comes close to the requirements of archaeometallurgical research.

The Laboratory for Archaeometallurgy deals with the reconstruction of past production techniques, i. e. the rolling of non-ferrous metals. For about a year now, the laboratory has been working on the production of sheet metal for the production of brass instruments, producing historical sheet metal alloys, casting them into slabs and processing them into sheet metal.

To this end, we have acquired a larger duo rolling stand with which we can manufacture sheet metal in special alloys by hand, which are no longer commercially available. This is of particular interest for the manufacture of instruments as well as for the production of countless archaeological and prehistoric metal sheet finds such as belts, situles, armour, helmets or shields. We are excites about this, because now we are no longer bound to the small selection of bronze sheets that are commercially available and yet already difficult to obtain. For the reconstruction of prehistoric and historic objects we can now produce the sheet metal that is required!.

The short film provides a glimpse of the trials and errors that are necessary when making historic non-ferrous sheet metal. By far not every metal alloy behaves in the same manner, some do not like being cast, some do not like being cold rolled. Others yet can only be rolled hot or have to be worked first with a hammer. It is an ongoing enterprise to make historic and prehistoric sheet metal, and a fascinating one, too. Turning a cast object into malleable sheet metal is something that a bronze founder does not do every day. In all cases the slabs and sheet metal to be has to undergo repeated heat treatment in order to produce good quality sheet metal. A process that is monitored by our lab by means of metallography…

no comments | posted in Archaeometallurgy, Metal casting, Science, sheet metal rolling

Feb

21

2014

Bastian Asmus

Image width 200 µm, PPL. Medieval copper smelting slag.

The first thing to do is to establish the number of different phases present in the sample. In this case there are five different phases.

If you managed to follow so far, you have now reached part seven part of the slag microscopy course. After sample prep, with find documentation, cutting, mounting, grinding, lapping and polishing we are now going to have a look at the tool to be used for the next sessions: the polarising reflected light microscope, also referred to as an ore microscope. Continue reading

no comments | tags: How to, microscopy, slag | posted in Analysis, Archaeometallurgy, Microscopy, reflected light microscopy, Science, slag